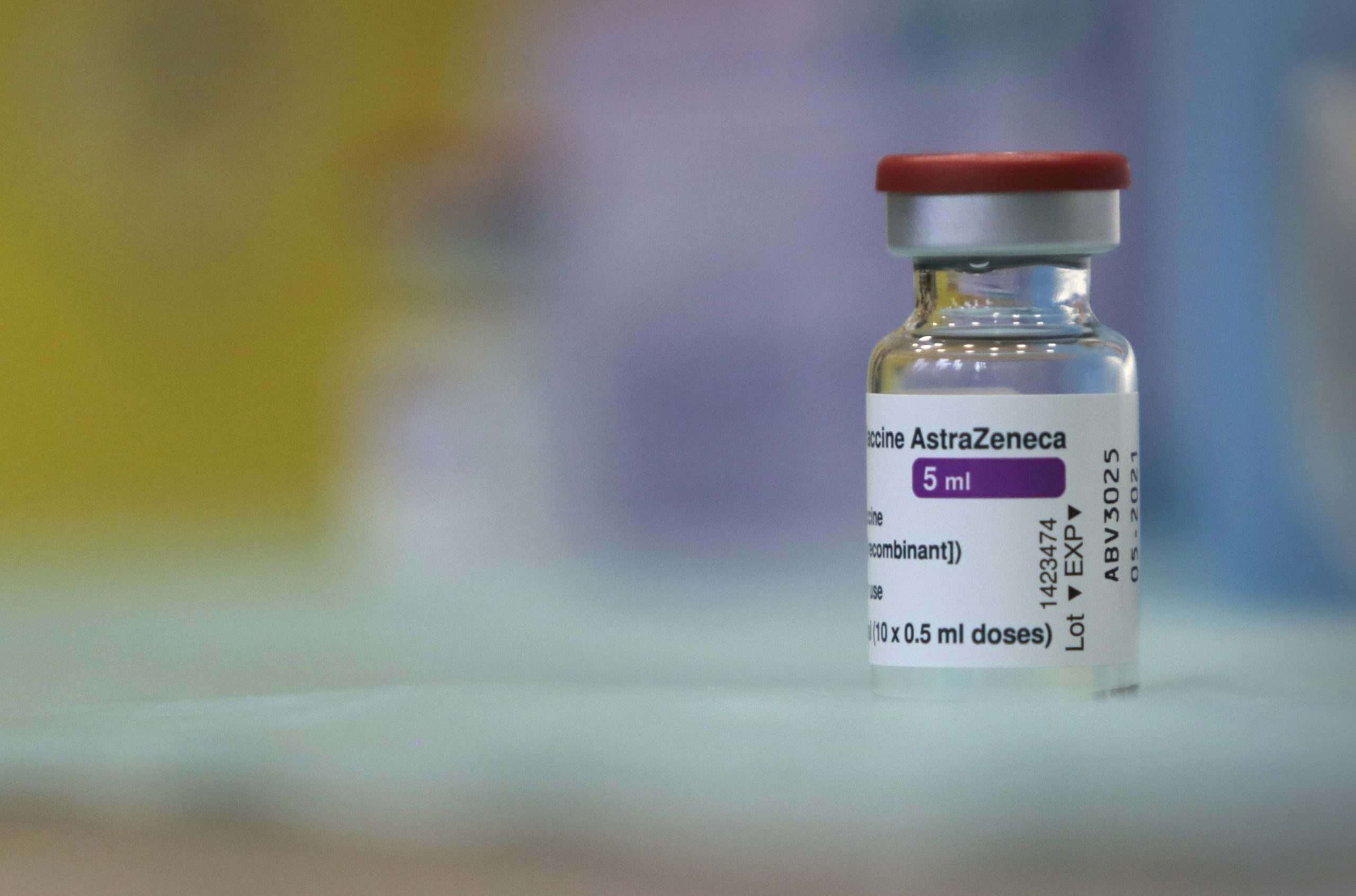

The South African health authorities have said that the government arrived at the decision to stop administering the AstraZeneca vaccine in the country because it showed less protection there than elsewhere because a SARS-CoV-2 variant that can apparently dodge key antibodies has become widespread. In the wake of the new finding, the country halted plans next week to launch the country’s first immunization campaign with the vaccine and may instead switch to a different one.

The stakes are high globally for this particular vaccine because its makers, AstraZeneca and the University of Oxford, hope it will be widely used in developing countries; they project they can produce 3 billion doses this year for about $3 each, far more product at a far lower price than any other vaccine shown to offer protection against COVID-19.

Yet the South African trial of the vaccine, conducted in about 2000 people, found such a low efficacy against mild and moderate disease, under 25%, that it would not meet minimal international standards for emergency use. But scientists are hopeful it might still prevent severe disease and death—arguably the most important job for any COVID-19 vaccine. That was impossible to tell from this placebo-controlled trial because it was small and recruited relatively healthy, young people—their average age was only 31. None of the subjects in either arm of the study developed severe disease or required hospitalization. The new results are a “reality check,” Shabir Madhi of the University of the Witwatersrand, the trial’s principal investigator, said at a Sunday evening press conference. “It is time, unfortunately, for us to recalibrate our expectations of COVID-19 vaccines, as well as how we go about deciding how to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic in South Africa as well as globally.”

COVID-19 vaccines made by Johnson & Johnson (J&J) and Novavax have also been shown to offer weaker protection against B.1.351 (also known as 501.V2), the SARS-CoV-2 variant that now causes the vast majority of all infections in South Africa, than against older variants. The vaccines’ efficacy against mild disease in South Africa was 57% for J&J and 49% for Novavax—lower than in any other country they were tested.

But the J&J vaccine, which was put to the test in the largest of the studies, convincingly protected against severe disease and death, even against the B.1.351 variant, and Madhi remains “somewhat optimistic” that the AstraZeneca-Oxford vaccine will, too; the results are not “all doom and gloom,” he said.

SARS-CoV-2–targeting antibodies triggered by the J&J vaccine were “very similar,” he said, to those elicited by the AstraZeneca-Oxford candidate, and the two vaccines are based on a similar technology: Both induce the body to make the spike surface protein of SARS-CoV-2 by delivering its genes in a harmless adenovirus. In a 44,000-person trial, the J&J vaccine prevented 85% of severe cases and completely protected people from hospitalization and death in several countries, including the 15% of the participants who were from South Africa.

The AstraZeneca-Oxford vaccine has produced confusing results from the start. Earlier preliminary results from trials in different countries showed a wide range of success rates against mild and moderate disease, but researchers have had difficulty interpreting the data because of differences in dose, intervals between doses, and variants in circulation. Just on Friday, a study suggested the vaccine offered strong protection against a more transmissible variant, B.1.1.7, that exploded in the United Kingdom and is now spreading fast throughout Europe.

In South Africa, the vaccine was given in two doses spaced 21 to 35 days apart. Antibodies made by vaccine recipients can typically “neutralize” SARS-CoV-2, meaning they can prevent it from infecting cells in culture experiments. But lab studies show they have far less power against B.1.351. Madhi stressed that the vaccine may still trigger a powerful T cell response, which can target and eliminate cells the variant manages to infect. He presented a test tube study showing how the mutations in the spike protein that allow B.1.351 to dodge neutralizing antibodies have little impact on T cell responses. “We believe that those T cell responses will still remain intact despite the mutations that exist in a B.1.351 variant,” Madhi said.

The AstraZeneca-Oxford vaccine trial, which ran from June to November 2020, found that starting 2 weeks after the second dose—when participants presumably were fully immunized—19 cases of mild or moderate disease developed among the vaccinated, versus 23 in the placebo group, resulting in an efficacy of 21.9%. That is far below the 50% minimum required for emergency use authorization in many countries.

Researchers sequenced the viruses that infected trial participants and found a strong link between vaccine failure and B.1.351’s explosion in South Africa. In people who received one dose of the vaccine before the variant began to spread widely, efficacy against mild and moderate disease was still a respectable 75%.

South Africa last week received 1 million doses of the AstraZeneca-Oxford vaccine and had planned to start to offer it to health care workers next week, which would have made it the first COVID-19 vaccine available in the country outside of clinical trials. Epidemiologist Salim Abdool Karim, who co-chairs the South African Ministerial Advisory Committee on COVID-19, said at the Sunday press conference that the rollout of the vaccine in South Africa “needs to be put on temporary hold” in light of the disappointing results. Karim explained to Science that the J&J vaccine should be available in South Africa in roughly the same time frame, so there should be no delay in starting to protect health care workers.

Barry Schoub, who leads a government advisory subcommittee on COVID-19 vaccines, says, “We may need to look at combinations of the [AstraZeneca-Oxford] vaccine with other vaccines, which may in fact synergistically give a very good response.”

At a World Health Organization (WHO) press conference today that discussed the new findings at length, a chorus of scientists and public health experts emphasized that the AstraZeneca-Oxford vaccine may still play an important role in South Africa and elsewhere. “The retention of meaningful impact against severe disease is a very plausible scenario” for the product against the B.1.351 variant,” said Katherine O’Brien, who heads WHO’s Department of Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals. The vaccine interval used in the trial was not long enough to build the most robust immune response, suggests Seth Berkley, who leads Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance and also helps run the COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access (COVAX) Facility that aims to increase access to COVID-19 vaccines for resource-limited countries. And Richard Hatchett, another co-leader of the COVAX effort who also runs the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, stressed a point made repeatedly: During an emergency, you use the best tools at hand. “Obviously there is a world full of the wild-type virus that the AstraZeneca vaccine is known to work against, so it is vastly too early to be dismissing this,” Hatchett said. “This is a very important part of the global response to the current pandemic and we need to find better vaccines, probably, against the variants that are emerging.”

Karim, who also spoke at the WHO press conference, said South Africa is now evaluating a proposal to roll out the AstraZeneca-Oxford vaccine in a stepwise fashion, first assessing whether it impacts hospitalization rates in the first 100,000 people to receive it. “We don’t want to end up with a situation where we vaccinated a million people or 2 million people with a vaccine that may not be effective in preventing hospitalization and severe disease,” Karim said.

The Oxford team that originally designed the vaccine says it has already begun to work on a second-generation candidate that targets the mutated spike protein of the B.1.351 variant. Oxford’s Sarah Gilbert, who leads that effort, suggested in a press statement that a reformulated vaccine might be given as a booster shot to the existing one. “This is the same issue faced by all of the vaccine developers, and we will continue to monitor the emergence of new variants that arise in readiness for a future strain change,” Gilbert noted.