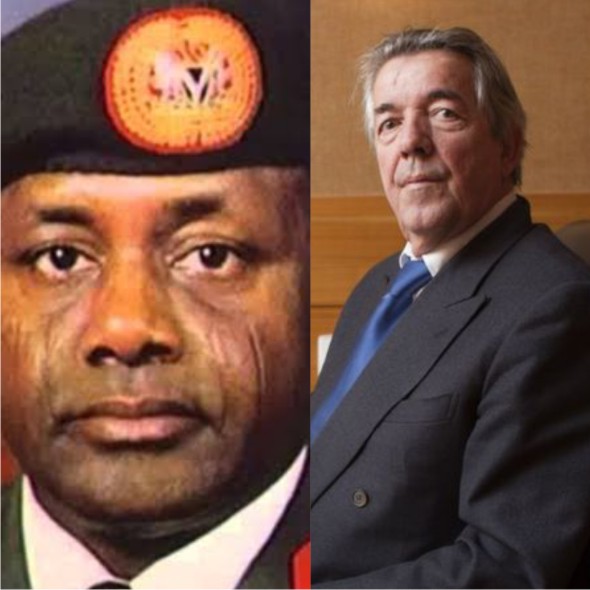

When Nigeria’s ex-head of state Sani Abacha stole billions of dollars and died before spending his loot, it prompted an international treasure hunt spread over decades. The man hired to get the money back tells the BBC’s Clare Spencer how the search took over his life.

In September 1999, Swiss lawyer Enrico Monfrini answered a phone call that would change his next 20 years.

“He called me in the middle of the night, and asked me if I could come to his hotel, he had something of importance. I said: ‘It’s a bit late but OK.'”

The voice on the end of the line was that of a high-ranking member of the Nigerian government.

‘Can you find the money?’

Mr Monfrini says the official was sent to Geneva by the Nigerian president at the time, Olusegun Obasanjo, to recruit him to get hold of the money stolen by Abacha, who ruled from 1993 until his death in 1998.

As a lawyer, Mr Monfrini had built up a Nigerian client base since the 1980s, working in coffee, cocoa and other commodities. He suspects those clients recommended him.

“He asked me: ‘Can you find the money and can you block the money? Can you arrange that this money be returned to Nigeria?’

“I said: ‘Yes.’ But in fact I didn’t know much about the work at that time. And I had to learn very quickly, so I did.”

To get started, the Nigerian police handed him the details of a few closed Swiss bank accounts, which appeared to be holding some of the money Abacha and his associates had stolen, Mr Monfrini wrote in the book Recovering Stolen Assets.

He said that a preliminary investigation published by the police in November 1998 found that more than $1.5bn (£1.1bn) was stolen by Abacha and his associates.

‘Dollars by the truckload’

One of the methods used for accumulating such a colossal sum was particularly brazen. Abacha would tell an adviser to make a request to him for money for a vague security issue.

He then signed off the request which the adviser would then take to the central bank, which would hand out the money, often in cash.

The adviser would then take most of that money to Abacha’s house.

Some was even taken in dollar notes “by the truckload”, Mr Monfrini wrote.

This was just one way Abacha and his associates stole huge amounts of money. Other methods ranged from awarding state contracts to friends at highly inflated prices and then pocketing the difference and demanding foreign companies pay huge kickbacks to operate in the country.

Abacha stole more than a billion dollars by pretending the money was needed for “security”. This went on for around three years until everything changed when Abacha died suddenly, aged 54, on 8 June 1998.

It is unclear whether he had had a heart attack or was poisoned because there was no post-mortem, his personal doctor told the BBC . Abacha died before spending the stolen billions and a few bank details served as clues as to where that money was stashed.

“The documents showing the history of the accounts gave me a few links to other accounts,” said Mr Monfrini. Armed with this information he took the issue to the Swiss attorney general.

And then came a breakthrough.

Mr Monfrini successfully argued that the Abacha family and their associates formed a criminal organisation.

This was key because it opened up more options for how the authorities could deal with their bank accounts.

Who was Sani Abacha?

*Fought in Nigeria’s army during the civil war.

*Key player in two coups before becoming minister of defence in August 1993.

*Became head of state in a military coup in November 1993.

*His government was accused of widespread human rights abuses.

*Nigeria was suspended from The Commonwealth after execution of nine human rights activists in 1995 by Abacha.

*Died unexpectedly on 8 June 1998, at 54 years old.

*Father of 10 children

The attorney general issued a general alert to all the banks in Switzerland demanding that they disclose the existence of any accounts opened under the Abachas’ names and aliases.

“In 48 hours, 95% of the banks and other financial institutions declared what they had which seemed to belong to the family.” This would uncover a web of bank accounts all over the world.

“Banks would deliver documents to the prosecutor in Geneva and I would do the job of the prosecutor because he didn’t have time to do it,” Mr Monfrini told the BBC.

‘Bank accounts talk a lot’

“We would find out on each account exactly where the money came from and/or where the money went to.

“Showing the ins and outs on these bank accounts gave me further information regarding other payments received from other countries and sent to other countries.

“So it was like a snowball. It started with a few accounts, and then a large amount of accounts, which in turn created a snowball effect indicating a huge international operation.

“Bank accounts and the documents that go with them talk a lot.

“We had so much proof of different money being sent here and there, Bahamas, Nassau, Cayman Islands – you name it.”

The size of the Abacha network meant a huge effort for Mr Monfrini.

“Nobody seems to understand how much work it entails. I have to pay so many people, so many accountants, so many other lawyers in different countries.”

Mr Monfrini had agreed a commission of 4% on the money sent back to Nigeria. A rate he insists was comparably “very cheap”.

Finding the money turned out to be relatively quick in comparison to getting it returned to Nigeria.

“The Abachas were fighting like dogs. They were appealing about everything we did. This delayed the process for a very long time.”

Further delays came as Swiss politicians argued over whether the money would just be stolen again if it was returned.

Some money was returned from Switzerland after five years.

Mr Monfrini wrote in 2008 that $508m found in the Abacha family’s many Swiss bank accounts was sent from Switzerland to Nigeria between 2005 and 2007.

By 2018, the amount Switzerland had returned to Nigeria had reached more than $1bn. Other countries were slower to return the cash.

“Liechtenstein, for instance, was a catastrophe. It was a nightmare.”

In June 2014, Liechtenstein did eventually send Nigeria $277m.

Six years later, in May 2020, $308m held in accounts based in the Channel Island of Jersey was also returned to Nigeria. This only came after the Nigerian authorities agreed that the money would be used, specifically, to help finance the construction of the Second Niger Bridge, the Lagos-Ibadan expressway and the Abuja-Kano road.

Some countries are yet to return the loot.

Mr Monfrini is still expecting $30m he says is sitting in the UK to be returned, along with $144m in France and a further $18m in Jersey. That should be it, “but you never know”, he says.

In total, he says his work secured the restitution of just more than $2.4bn.

“At the beginning people said Abacha stole at least $4-$5bn. I don’t believe it was the case. I believe we more or less took the most, took a very large chunk, of what they had.”

He has heard rumours that the Abacha family are not so wealthy any more.

Or, as he puts it: “They are not swimming in money like they used to do in the past.”

When he looks back, he seems satisfied with his work.

“When I speak to my very many children about this case, I tell them I found money and I blocked the money, I persuaded the authorities to go after these people and get the money back to the country for the good of the Nigerian people.

“We did the job.”