While Nigeria prepares for a revenue shortage in 2021, with plans to borrow about a quarter of the year’s budget expenditure, the country will spend around N7.8 billion on entitlements, severance allowances and other perquisites to the nation’s former leaders, details of the assented 2021 budget have shown.

The planned 2021 spending is the second-lowest amount that will be allocated to retired top government officials since 2017, when N5.9 billion was budgeted as gratuity for them.

The money is a yearly ritual in the nation’s budgetary cycle, and by the end of this year, it would have cost Nigeria about N68.8 billion in five years.

This year, of the total N7.8 billion, former heads of state, presidents and their respective deputies will earn a combined entitlement of N2.3 billion. This is the same amount that has been approved for the former leaders since 2017, save 2018 when they got N7.3 billion.

The appropriation is in accordance with the remuneration for the former presidents‘ act, which offers a slew of luxuries which have been faulted by some, especially because four in every ten Nigerians earn less than N377 per day, and the unemployment rate reached a record high last year as the country keeps struggling to diversify its economy to shore up its revenue base.

As upkeep allowance, the act mandates the monthly payment of N350,000 to former presidents and N250,000 to former vice-presidents and chiefs of general staff, and this is subject to a review whenever there is an increase in the salary of the serving president.

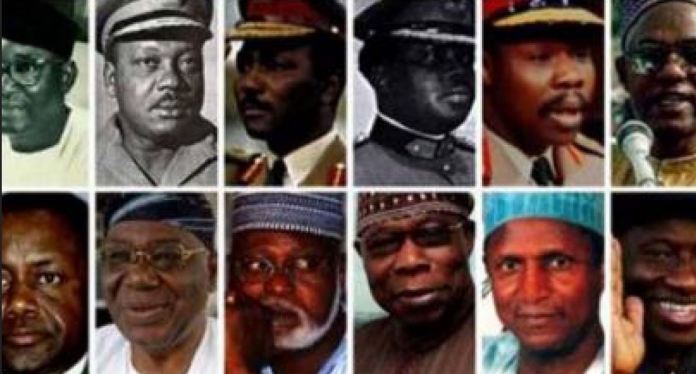

Nigeria has had fourteen presidents, prime minister and heads of state, all men, including incumbent President Muhammadu Buhari, since independence in 1960.

Inclusive of Mr Buhari, seven of them are living: Yakubu Gowon, Ibrahim Babangida, Ernest Shonekan, Abdulsalami Abubakar, Olusegun Obasanjo and Goodluck Jonathan.

The deceased former heads are: Tafawa Balewa (only prime minister), Nnamdi Azikiwe (first ceremonial president), Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi (first military head of state), Murtala Mohammed, Shehu Shagari, Sani Abacha and Umaru Yar’Adua.

The nation has also had 14 vice presidents and deputy heads of state, again all men, including two different deputies under the Ibrahim Babangida military junta – Ebitu Ukiwe, 70, and Augustus Aikhomu, who died in 2011 aged 71.

Seven of them are alive, including Olusegun Obasanjo and Goodluck Jonathan, who would later become presidents themselves. Others are Ebitu Ukiwe; Mr Abacha’s deputy, Oladipo Diya; Atiku Abubakar, Namadi Sambo, and incumbent Yemi Osinbajo.

The nation’s deceased former vice-presidents include Mr Ironsi’s deputy, Babafemi Ogundipe; Mr Gowon’s de facto deputy who died in 1991, Joseph Wey; Shehu Yar’Adua, who was Mr Obasanjo’s deputy in the latter’s military stint; Nigeria’s first democratically elected vice-president, Alex Ekwueme; Tunde Idiagbon, Mr Buhari’s deputy as head of state; Augustus Aikhomu; Mike Akhigbe, Nigeria’s last military deputy head of state.

Living presidents and their deputies are, at the expense of the federal government, entitled to at least six security details and personal aides; well-furnished office and a five-bedroom apartment in any location of their choice; vehicles replaceable every four years; diplomatic passport for life; free medical treatment, which may be abroad where necessary, for themselves and their immediate families; thirty days all-expense-paid annual vacation within and outside Nigeria.

The families of all deceased former presidents are, meanwhile, entitled to an annual allowance of N1 million payable as N250,000 per quarter, while the families of deceased former deputies get N750,000 per annum payable in the sum of N187,500 per quarter.

“The allowances shall be applied for the up-keep of the spouse and education of the children of deceased former heads of state and deceased former vice-presidents up to the university level,” the act reads.

However, if the spouse of the deceased leader remarries, they stop getting the allowance.

Other expenses

In the same vein, the nation’s retired heads of service and permanent secretaries will get a combined N4.5 billion as benefits this year, the exact amount that has been shared among them since 2019.

This is an increase from the N3.6 billion the former officials got in 2018, and N2.6 billion in 2017.

Also, for the fifth year running, retired heads of government agencies and parastatals will share among themselves N1 billion as severance benefits.

Allocation over the years

A review of the approved budgets since 2017 showed that the country has spent about N70 billion on the severance benefits for its former leaders.

While the financial obligation will cost the country N7.8 billion this year, it cost more in the preceding years.

In 2020, it cost Nigeria N11.7 billion. This amount is inclusive of the N3.9 billion budgeted as additional retirement benefits for chief of defense staff, service chiefs, generals, colonels and army warrant officers.

The amount is nonetheless way lower than the N31.5 billion spent in 2019, which included the severance package of N23.7 billion for the incoming and outgoing federal lawmakers and their aides.

Nigeria spent N11.9 billion for similar purposes in 2018; and N5.9 billion in 2017, which is the lowest in five years.

Nigeria has hardly ever mulled the possibility of abolishing or significantly reducing the pension packages for its former leaders and it continues to give little recourse to economic reality which informs why it will sell some government-owned properties and borrow to finance the 2021 budget, a quarter of which will go into debt payments.

Critics have often argued that cutting the cost of governance is the brave step the country has refused to take to boost its earnings.

Over the years, the national minimum wage stalled at N18,000 (about $50) until it was increased to N30,000 (about $80). Yet, some states have not met either benchmark.

Still, like former federal leaders, former state governors and their deputies get extravagant allowances as pension even as their states grapple with the economic downturn.

Stung by this economic downturn, especially as it has been dented a hard blow by the coronavirus pandemic, some states have taken austere measures by repealing the act. A few more are underway.

But the larger number of other state governments that have maintained the status quo is a mirror reflection of what obtains in the larger Nigerian society.