African health ministers today launched a campaign to ramp up awareness, bolster prevention and care to curb the toll of sickle cell disease, one of the most common illnesses in the region but which receives inadequate attention.

More than 66% of the 120 million people affected worldwide by sickle cell disease live in Africa. Approximately 1000 children are born with the disease every day in Africa, making it the most prevalent genetically-acquired disease in the region. More than half of these children will die before they reach the age of five, usually from infection or severe anaemia.

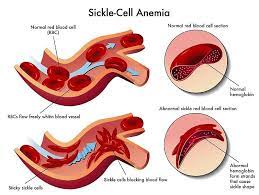

Sickle cell disease is an inherited blood disorder that shortens red blood cell survival, causing anaemia—often called sickle cell anaemia. Poor blood oxygen levels and blood vessel blockages in people with sickle cell disease can cause extreme pain in the back, chest, hands and feet as well as severe bacterial infections.

In the African region, 38 403 deaths from sickle cell disease were recorded in 2019, a 26% increase from 2000. The burden of sickle cell stems from low investment in the efforts to combat the disease. Many public health facilities across the region lack the services for prevention, early detection and care for sickle cell disease. Inadequate personnel and lack of services at lower-level health facilities also hamper effective response to the disease.

The campaign, launched at a side-event on enhancing advocacy on sickle cell disease during the Seventy-second World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Committee for Africa—the region’s flagship health meeting, aims to shore up political will and engagement as well as financial resources for sickle cell disease prevention and control across the region. It also seeks to raise public awareness of the disease in schools, communities, health institutions and the media and advocate stronger health systems to ensure quality and uninterrupted services and equitable access to medicines and innovative tools.

“Most African countries do not have the necessary resources to provide comprehensive care for people with sickle cell disease despite the availability of proven cost-effective interventions for prevention, early diagnosis and management of this condition,” said Dr Matshidiso Moeti, WHO Regional Director for Africa. “We need to shine the spotlight on this disease and help improve the quality of life of those living with it.”

Due to the absence of newborn screening programmes and surveillance across the region, there is a lack of accurate and reliable data on the disease. Additionally, data collection for sickle cell disease is not included in most national population-wide surveys. These data gaps have negatively impacted the prioritization and allocation of resources for the disease.

Beyond its public health impact, sickle cell disease also poses numerous economic and social costs for those affected and their families and can interfere with many aspects of patients’ lives, including education, employment, mental and social well-being and development.

“We can no longer ignore the significant burden caused by sickle cell disease,” said Dr Moeti. “We must do more to improve access to treatment and care, including counselling and newborn screening by ensuring that programmes are decentralized and integrated with services being delivered to communities and at primary health care level.”

Dr Moeti stressed the need for greater investment and stronger collaboration and partnerships to help stem the tide of rising cases of sickle cell disease in Africa.

In addition to WHO, the new campaign is being supported by partners including the World Bank, the United States Department of Human and Health Services, Novartis Foundation, Global Blood Therapeutics and Sickle in Africa.