With Brent crude at $50 a barrel, energy giants are fighting to keep their place at top table. Saudi Arabia is burning through its foreign reserves at an unprecedented rate as it struggles to cope with plummeting oil prices and the soaring coasts.

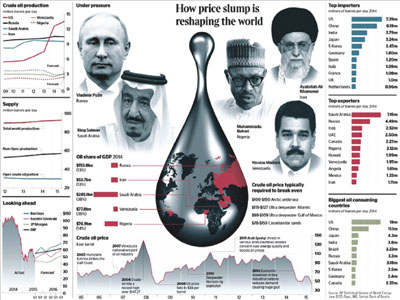

The price of oil sank to below $50 a barrel last week, the lowest in six years, draining Gulf states of their spending power – but hitting Russia and other producers harder still. Venezuela and Nigeria face bankruptcy and there are fears that the collapse in the oil price could trigger a seismic shift in the global balance of power.

Saudi Arabia took $2 billion a week out of its foreign reserves between the end of September 2014 and June 2015, with King Salman, who came to power in January unleashing an intensive military onslaught against Iranian – backed Houthi rebels in Yemen and funneling arms to opponents of President Assad in Syria, Saudi Arabia’s monetary agency put its foreign reserves at $672 billion at the end of June, down from $746 billion in September 2014.

“It’s coming down fast,” David Butter, an energy expert at the Chatham House think tank, said. Evidence of that, he said, was Saudi Arabia’s decision to borrow $5 billion in the sovereign bond market last week, the first time in eight years it has had to do that.

The world’s top oil exporter and the de facto leader of the 12-nation Organisation of Oil Exporting Countries (OPEC) cartel, Saudi Arabia has shown in the past that it is prepared to use oil money to quell social unrest. It was able to nip Arab Spring protest in the bud by paying off demonstrators and spending $130 billion to raise salaries and boost social spending.

Many observers believe that Saudi Arabia has brought the oil crisis on itself by refusing to curb production to drown out competition from fracking by the United States (U.S.) As a result, the price has fallen from $50 now, and the effect is reverberating around the world – from the slums of Caracas to the battlefields of Syria and Iraq from the Russian Arctic to the Pearl River Delta in China.

On the plus side, a lower oil price has boosted the world economy by diverting consumer spending away from energy costs. “The world’s consumers will be much better off, especially the poor, who spend a higher proportion of their income on energy,” said Lief Wenar, at King’s College London, the author of Blood Oil. “Big importers such as India, China, Japan and many developing countries will be winners. It should help growth and cut the cost of basic goods”.

In Venezuela which has a world’s biggest oil reserves the opposite applies. The country is spiraling into hyperinflation and crime is rising amid rising fears of a possible debt default – all of which could bring an end to the presidency of Nicolas Maduro as early as December, when parliamentary elections are due to be held.

In Russia, where oil and gas account for 75 per cent of exports and more than half of budget revenues a plunging economy and a struggling current are threatening living standards – giving nourishment to nationalists and others eager to whip up an anti-western war in Ukraine.

For every dollar the oil price falls, Russia loses $2 billion, according to Professor Wenar. “If prices stay low, I expect more anti-western rhetoric and a ramping up of the war, to distract public attention and heap blame on the West,” he said. Russia’s economy shrank 4.6 per cent in the second quarter, its worst performance since 2009.

The smaller Middle Eastern and African oil exporters that lack Saudi Arabia’s deep pockets are suffering worst. Algeria, which relies on oil and gas for 97 per cent of export revenues, is already battling an Islamist insurgency and could find itself overwhelmed, like neigbourhing Libya, if its fragile economy crumbles.

Gulf states, such as Bahrain and Oman, which rely heavily on Saudi cash and patronage, fear a revival of civil unrest of religious strife if the oil crisis drags on. “Both countries look like last time they may not be able to count on Saudi support”, Professor Wenar said.

Iran, too, is feeling the pressure – one of the reasons why it was willing to strike a deal over its nuclear programme. “Iran was partly driven to the negotiating table by lower oil prices,” a Mumbar think thank said.

Iran government is struggling to pay for its fight against Islamic States (ISIS), which controls the leading city of Mosul and swathes of territory in the north of the country – but it will take comfort from the fact that the jihadists, too, will be feeling the squeeze as most of their income is from stolen Brent crude.

Other OPEC members such as Angola and Nigeria face deepening economic hardship fueling insurgences from groups such as Boko Haram.

Saudi Arabia, where two thirds of the population is aged under 30, might face social upheaval in the near future, especially if an economic slump brings fewer jobs and opportunities for the young – and civil unrest would quickly fuel Islamist militancy.

By Olisemeka Obeche

[divider]