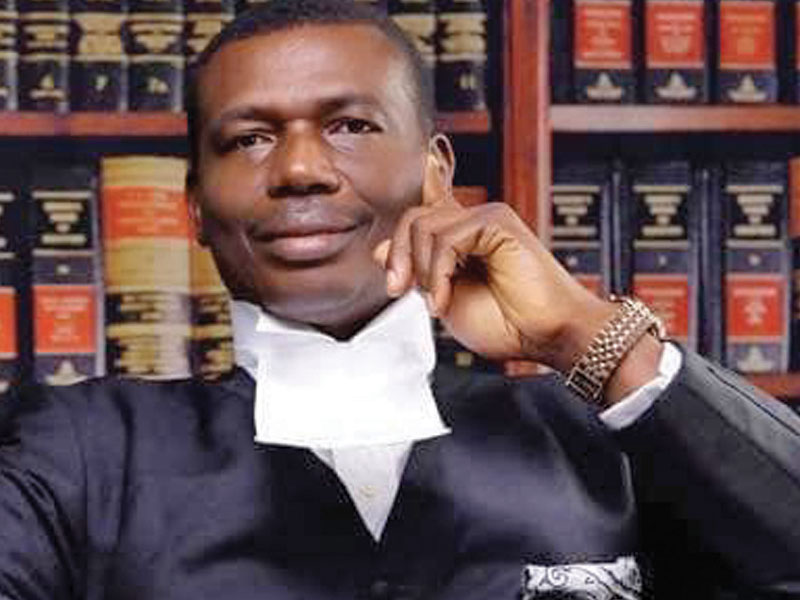

By EBUN-OLU ADEGBORUWA

ESTABLISHED as one of the first generation universities, the University of Lagos (UNILAG), has come to occupy its pride of place in the history of education in Nigeria, boasting of nursery, primary, secondary and tertiary places of learning, all combined in one institution. In 2019, UNILAG ranked 801-1000 in the global universities status, according to the World University Rankings. It moved up in 2020 to 601-800, amongst 1527 institutions from 93 countries, drawing data from over 1,900 leading research universities and more than 22,000 academic reputation survey responses.

The exercise analysed over 13 million research publications and more than 80 million citations over five years. UNILAG had become a brand name and national pride for Nigeria and indeed Africa. It won millions of dollars in research grants across the globe and had become one of the institutions of first choice amongst admission seekers and job recruitment experts. That was before August 12, 2020, when the unthinkable happened.

Just like a bolt from the blues, the news broke that the Governing Council of the University had met (in Abuja!) to remove the UNILAG Vice-Chancellor. As the nation was swallowing that shock, news broke out again that the same Governing Council had appointed an Acting Vice-Chancellor. It was now looking like some script for a celebrated movie.

The question on everyone’s lip was: could this be happening to UNILAG? The same UNILAG that we all know? We then started to get the details, as worrisome as they emerged. It transpired that there had been a long-drawn battle between the Pro-Chancellor of the University and also the Chairman of the Governing Council and the Vice-Chancellor and also the head of the Management Team of the University, over several issues, including but not limited to control of funds, award of contracts, management of the university, etc.

Elders had intervened to no avail, the Alumni Association had mediated without success and the regulatory authorities, including the National Assembly, had one form of intervention or the other, without meaningful result. What happened?

The Pro-Chancellor and the Vice-Chancellor do not see eye to eye, as fundamental disagreements placed hurdles between their mutual agreement and this strayed over to meetings of the Governing Council, where they both had loyalists. Of course, as they say, when two elephants fight, the grass suffers.

The academic staff of UNILAG viewed the actions of the Pro-Chancellor as unnecessary interference with the autonomy that they had fought for many years ago and they joined forces with the Vice-Chancellor, to resist what they termed as ‘high-handed’ posture of the Governing Council in the internal affairs of the university.

That was before the national ASUU embarked on a nationwide strike, which is still ongoing. Things got to a boiling point, when the UNILAG chapter of ASUU declared the Pro-Chancellor a persona non grata, an action that was considered extreme, having regard to the express provisions of the Constitution on the right to freedom of movement. But ASUU stood its ground and did not allow the Pro-Chancellor access to the university. Perhaps this was what informed the Abuja option for the meeting of the Governing Council.

The details of what transpired at the Abuja meeting of Council are not out yet, but suffice it to mention that the outcome of that meeting did not meet the expectations of the academic community and indeed many Nigerians watching from the sidelines. Not so much for the removal of the Vice-Chancellor but rather the strange procedure adopted to effect it, which many saw as a clear violation of the extant laws on the subject.

I have been part of the struggle for university autonomy and academic freedom whilst in the university as a student leader. It took many strike actions, negotiations and compromises, for the authorities to agree to let the universities run themselves.

One of the ways of achieving that autonomy is in the composition of the Governing Council of the universities such that the academic community, through its Senate and Congregation, would have a say in major decisions of the Council.

Looking through the website of the regulatory NUC however, for the composition of the Governing Councils of the universities, that of UNILAG became a puzzle, as it had no national spread. It had three members from the South-West, two of them from the same law firm, it had no representative from the South-South and the South-East. As of the time of the Abuja Council meeting, the representatives of Senate and Congregation had dwindled, due to tenure expiration or retirement. Then the Vice-Chancellor and his Deputy were asked to vacate the meeting.

In essence, the decision of Council of August 12 2020, did not have the input of the academic community of UNILAG. It took us back decades, having regards to the gains of the struggle for university autonomy, over the years.

There is no issue on the authority of Council to take any decision it deems appropriate on any issue covered under its mandate, especially where it has to do with alleged improprieties, subject of course, to proper proof.

However, the law regulating the procedure for the removal of a Vice-Chancellor of any university was intended to be representative of the academic community of the university, to follow due process of law in the process of removal and also to achieve total transparency. This is because the Vice-Chancellor is the chief executive officer of the university, next in rank to the Pro-Chancellor. To remove such a principal officer of the university should not be made to look like some beer-parlour coup d’etat. Why not lay the allegations bare, make the intention to remove him plain (if there is nothing to hide) and then subject the person to thorough scrutiny by his peers?

Why should there be any drama in removing a Vice-Chancellor, when the process has been simplified by the enabling law? Can the Council be the accuser, the investigator, the prosecutor and the judge all at the same time?

In this case, there was no complaint from the university community against the Vice-Chancellor; rather, it was the Council that raised the allegations suo motu and it then set up its own Committee to investigate the allegations. The Council thereafter sat to pass sentence on its own report. And to make matters worse, those members of the Committee that investigated the allegations also partook in the decision to remove the Vice-Chancellor. How can this be?

What the Council was expected to do by law was to consult the Senate and the Congregation of the university, to nominate their members to be constituted into a Committee to investigate allegations against the Vice-Chancellor.

Apart from guaranteeing autonomy for the universities, I believe that part of the major reasons for this process is to ensure that the university community is carried along, so that in the event that the Vice-Chancellor is eventually removed from office, it should not be difficult to implement the removal, as they would have been carried along through their representatives from the Senate and the Congregation. Part of the current crisis in the UNILAG case is that the decision to remove the Vice-Chancellor is viewed as a coup against the university community. So long as due process has not been followed, there can be no merit in any allegation raised to warrant the decision, as something cannot be put on nothing and be expected to stand, it must collapse. What made the case of UNILAG worse is that the law expressly forbids the appointment of a sole administrator for any university, as was done by the Council in this case, no matter the excuse. To have proceeded to appoint an Acting Vice-Chancellor in flagrant violation of the law and without consulting the Senate of the university was the greatest act of impunity perpetrated by the Council, worse even than the allegations against the Vice-Chancellor.

It was against this background that the federal government, through the Visitor to the university, intervened to restore law and order in the university. A visitation panel was then constituted to investigate all issues surrounding the crisis. All parties attended before the panel, to give their respective accounts as to what truly transpired, documents were tendered and questions were asked and answers given. Given the urgency of the occasion, the panel was to submit its report within two weeks. We all followed the proceedings of the panel with great expectations, as its members worked night and day to deliver as instructed. Indeed, the panel submitted its report within record time and we all heaved a sigh of relief, expecting the outcome to be made public so that permanent peace will return to the university.

Alas, it is now over one month since the panel submitted its report and nothing has been heard from the supervising Ministry of Education, which had asked the panel to work day and night. Why should it take one month for the consideration of the report of a panel that sat for only two weeks?

It stands logic on its head, for the authorities to ask the sole administrator appointed by Council to step down only for the university to be saddled with an Acting Vice-Chancellor in perpetuity, even though the occupant has succeeded in maintaining peace within the university since her appointment.

There is no need for the crisis in UNILAG to fester; the government must confront the monster and summon the will power to do the needful. We cannot spend public resources on a panel, gather serious-minded people to work themselves out and then turn around to sit on their efforts.

The public is entitled to know the truth about the situation in UNILAG, because it will be a bad precedent for our institutions, should there not be a definite outcome on the mind of the authorities on the events that happened in that great university.

The suspense pervading UNILAG should be vacated with dispatch, parties should know their fate and the process brought to a fruitful end. As we say in law, interesti publicae ut sit finis litum (it is in the interest of the public that there must be an end to litigation).